Context Engineering: The Secret Behind Every AI Conversation

Naveen

Naveen- 0

Every time you chat with an AI like ChatGPT or Claude, something fascinating happens behind the scenes—it completely forgets you the moment the conversation ends. Sounds harsh, right? But here’s the thing: this isn’t a bug, it’s just how these systems work. So how do they manage to keep a conversation going when you send that next message? The answer lies in something called context engineering, and it’s absolutely fundamental to how we build sophisticated AI systems today.

By the end of this article, you’ll understand how prompts, memory, files, and tools all coordinate together in context engineering. Whether you’re just chatting with ChatGPT or building full-blown agentic systems, this is critical information that’ll help you get better results from any LLM you work with.

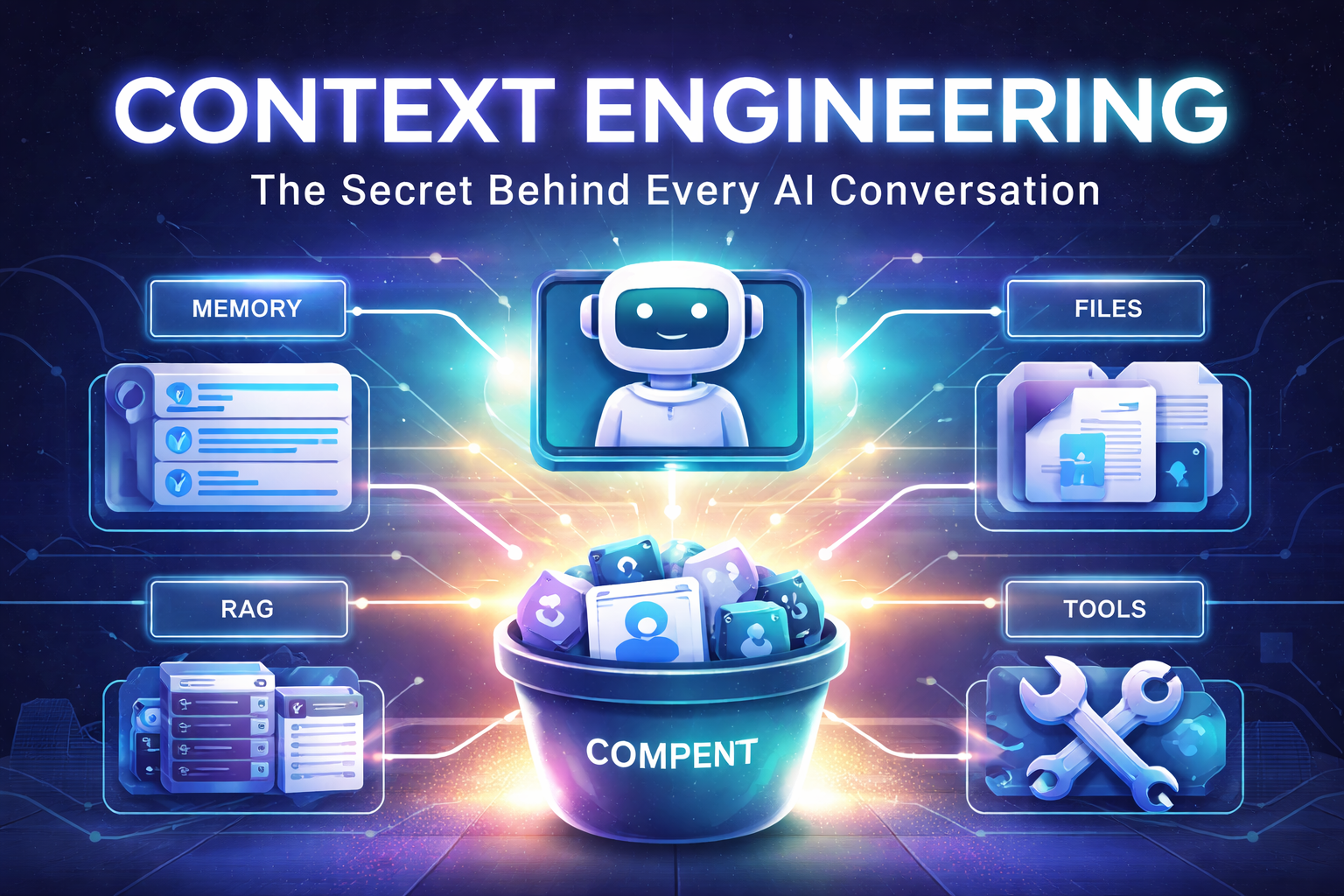

The Big Picture: What Is Context Engineering?

Let me paint you a picture. Imagine meeting someone with complete amnesia every single time you see them. The only way they can know who you are is if you introduce yourself from scratch—every. single. time. That’s essentially what happens with LLMs.

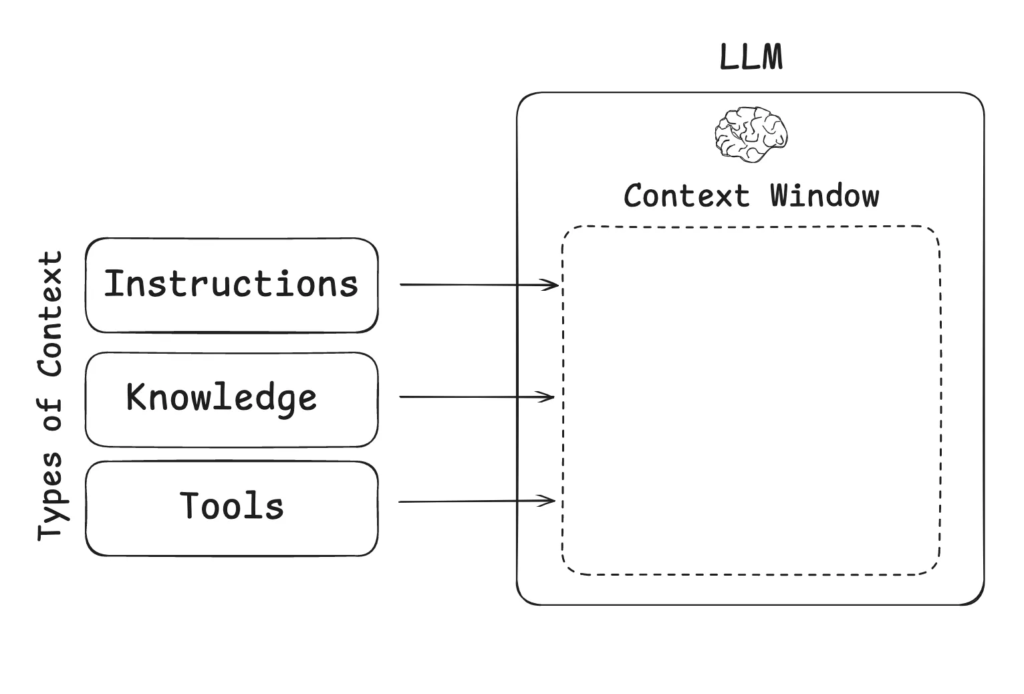

You’ve probably heard people talk about “context windows” and managing your context without bloating it. But here’s what’s actually happening: every time you talk to an LLM, you have to send in literally everything it needs to execute the task you’re asking for.

Think about it this way—if you’re asking “Give me the action items from my notes,” and you uploaded those notes in your previous message, guess what? The LLM has completely forgotten about them. So underneath the covers in something like ChatGPT, they’re managing that context for you automatically.

Context is really just a bucket of everything that goes in. It’s a container concept for all the information being sent in that the LLM has a chance to use to answer your question.

The Building Blocks of Context

Let’s break down the different parts inside of context. Trust me, the better you understand this, the better you’re going to be at wrangling what the LLM gives you back—whether you’re just chatting with ChatGPT or building complex agentic systems.

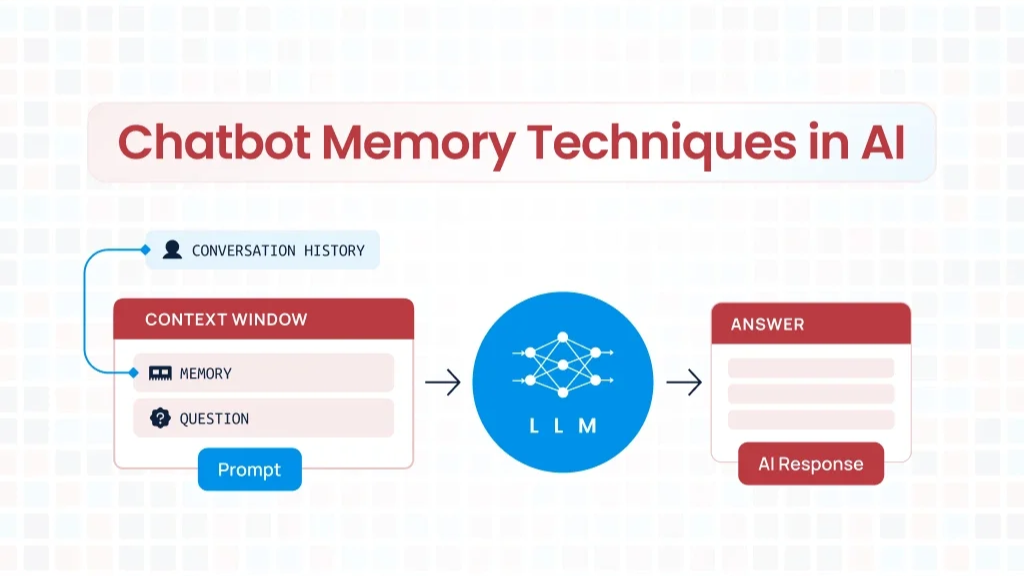

1. Memory: The Historical Context

Memory is exactly what it sounds like—some context from the past that we have. It’s literally the same concept here with LLMs.

Here’s a real example: Let’s say I upload a file to ChatGPT and ask, “Give me a summary.” Then I follow up with, “Can you give me the action items from it?” For that second request to work, the entire conversation needs to be sent back to the LLM so it can make a decision on how to extract those action items. This is what we call historical conversation, and it happens in ChatGPT all the time.

Memory also includes possible personal information. ChatGPT might know what region you’re in and be able to construct dates appropriately and insert those into the information.

But here’s where it gets tricky. As an engineer (and really, as a user), this is the active part you have to manage. For example, I can have thousands and thousands of interactions with ChatGPT back and forth. At some point, I’ve had too many and it can’t all fit in there.

So what are they doing to make sure the whole conversation is within the brain when the brain has to answer your next question? Well, unfortunately, the answer to that is engineering. What they’re really doing is trying to figure out how to summarize the previous conversation and pull out the most important nuances, then send in the last maybe 10 messages.

The most recent messages get weighted the heaviest, thinking that’s where the majority of the conversation is happening right now, so let’s make sure we send all of that in.

This is where we start seeing something like drift. If you’ve ever noticed, the longer a conversation you have in the same chat context, the less it conforms to the things you’ve asked it to do in the past. You have to remind it: “No, didn’t I tell you not to do that?” or “I don’t want that kind of information. Don’t use tables. Always use a canvas.” All of that kind of stuff with ChatGPT happens because of this summarization or management of the conversation history.

2. Files: The Obvious One

Files are really obvious. This is an easy one. You’re actively supplying files—like when you drop a file onto ChatGPT and say, “Here’s my notes. Please summarize them.”

Another one that I love doing is screenshots. When I have a screenshot and I really want to ask questions about it—believe it or not—in some cases, you’ll see a prompt later that I built just from one of these pictures. I basically gave the slide to ChatGPT and said, “Can you make a prompt out of this for me?” And it created the prompt and we’re going to use it.

Hot tip: If you’re not using screenshots with AI, definitely start. They’re absolutely critical.

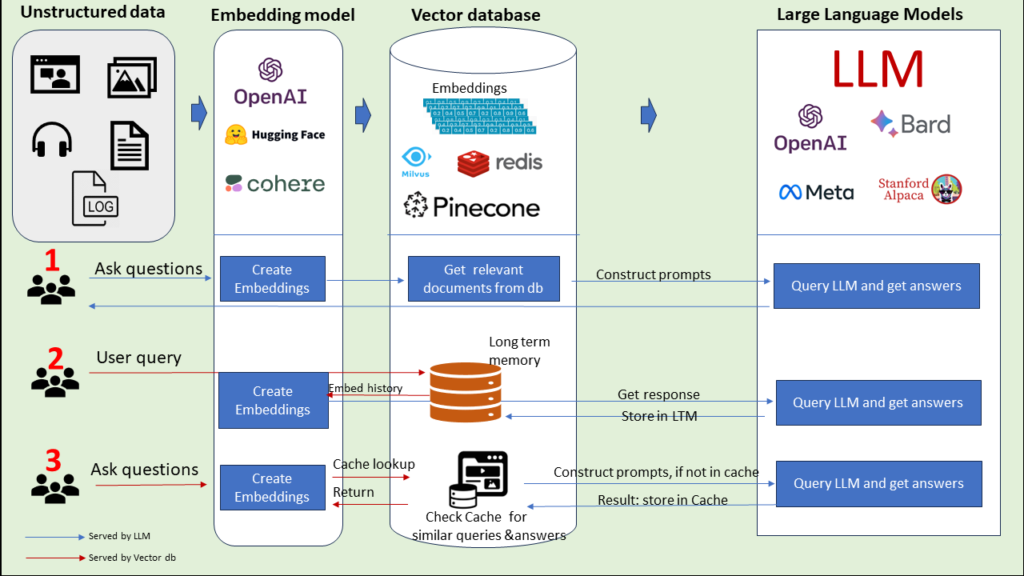

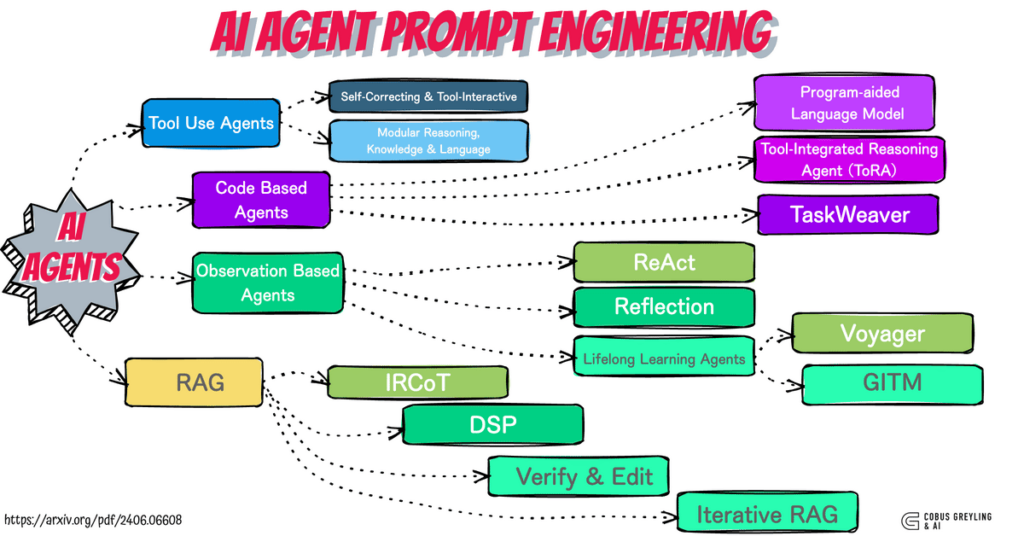

3. RAG: The Behind-the-Scenes Helper

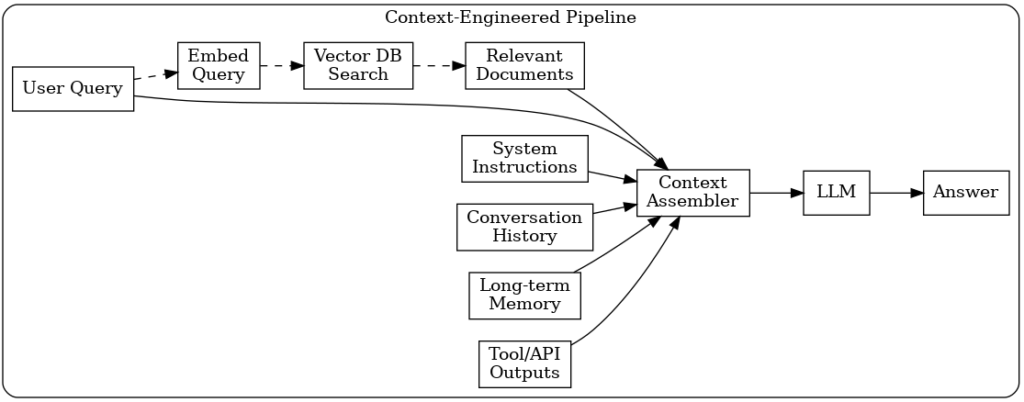

RAG is a special term—Retrieval Augmented Generation—which just means that as you’re asking a question, the engineers before it gets to the LLM are saying, “Okay, what do I think they’re asking about?”

Let me give you an example. Imagine I go to your website and I say, “I want the top candy released last month.” If you just sent that to ChatGPT, I’m going to get some random version of that answer. But you run a store and you actually sell three different kinds of candy, and you want those to show up when somebody asks this question.

So the first thing you do when my request comes in is have an LLM take a look at it and say, “Do I have anything in my data that seems to kind of help answer this question?” If so, they don’t send that information back to you directly—they actually take the records that they find in their database and they put them into the context quietly.

So the whole question goes in—”tell me about the top candy”—as well as the three things that they found in their database that they’ve shoved into this context. Those are going to, of course, come back as part of the answer. Pish posh, I’m buying your candy. Congratulations.

4. Tools: The Power Multipliers

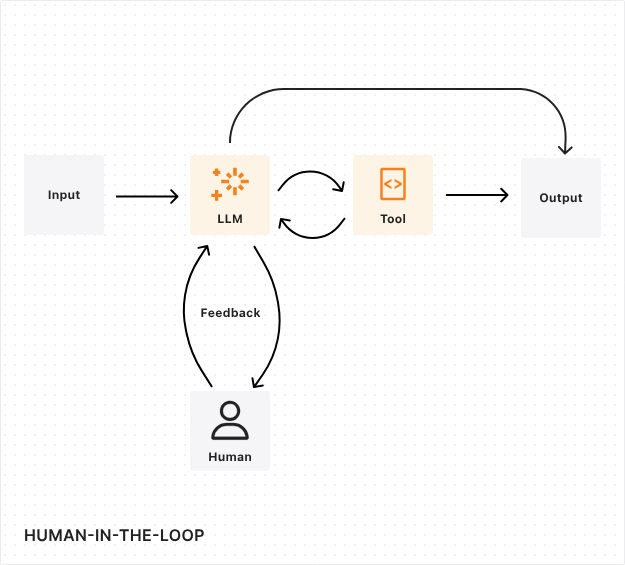

Tools are critical. You might have heard about tool calling if you’ve had your ear to the ground around here. Different LLM models know how to perform tool calling, and I’m actually about to show you exactly what that means.

When you talk about providing tools to an LLM, remember: an LLM is just a decision engine trying to come up with an answer or a string of words or an image or something like that. It’s not actually going to run those tools. (Okay, some of these new models actually have a facility to be able to execute these tools internally, but let’s talk about the very general case.)

What you’re really asking is for the LLM to give you a response that says, “Oh, you know what I think you should do? I need to get whatever is returned by calling this tool. Please go run that for me. Gather the responses and give those back to me”—very similar to RAG, by the way—”and then I’ll answer the question that you asked.”

Here’s how it works in practice:

On the left side of your request, you might have:

- System info: “You’re a helpful assistant”

- Available tools: “Here’s a web search tool. This is a simple web search tool. You just need to provide a prompt for it.”

- User question: “What’s the weather in London tomorrow?”

Now, you haven’t actually given it the web search tool. You’ve just told it there is a web search tool that you’re aware of and here is what it’s good for.

The LLM chews on that question. It says, “Oh, weather tomorrow? Well, I don’t know much about tomorrow. I’m kind of a past tense kind of thing. Let me check this web search tool.”

So what it replies is: “Oh, you need to call this tool. Here’s a tool call.” And the arguments that you send into that tool are “weather in London tomorrow.”

Your system makes that call, gathers the responses, puts those in basically as files (just like RAG did), sends it back to the LLM. The LLM chews on all of that again and gives us a response using the results that came back from that web search tool. Nice and easy.

Prompt Engineering: The Big One

This one’s called out specially for a reason—it’s a big one. Prompt engineering is really an important thing, and it’s actually always going to be important when we’re speaking plain language to systems that have to interpret the language we’re using.

That might look like how you ask the question or what instructions you give to it or which words are in which order. That’s a little less frequent these days—models have moved on from that kind of level of specificity and they’re a lot more generalized. However, they still really care about what you’re asking in your prompt.

Why Separate All These Moving Parts?

You might be wondering: why are we talking about all of these moving parts when we’re just saying “be careful what you put into the system”? It matters what you get out of it. That’s pretty obvious, right?

Here’s the thing: I’m separating these—and a lot of us are separating these—as explicit areas of interest most specifically so that you can see them as a dial.

Once you start engineering with these, even when you’re just working with ChatGPT, you need to understand the different dials you have to turn. You’re going to be able to get much better performance out of these things if you actually perceive the different elements that are going into the context or the prompt as things that you can adapt and test.

“If I turn this one a little bit, does it get better or worse? And this one a little bit the other way. Does it get better or worse?”

That’s what this is actually all about.

The Anatomy of a Prompt

We all know very well that if all you did was go to ChatGPT and say, “Where did I leave my keys?” you’re not likely to get a great answer back from that.

But if you went to ChatGPT and said, “I went to my mom’s house. I ate at Burger King. I drove back home and now I can’t open the door. Can you help? Where did I leave my keys?” It’s probably going to tell you, “Have you checked your car?”

Now let’s move into the different parts of the prompt. We want to separate them as much as we can. Really, each prompt you’ve sent—and you’ve sent thousands of them at this point—are just a big string. So why would it be so separable like this?

Well, this is the fun part. Let’s take a look at what you might put into a prompt. Engineers are already using these techniques:

1. Role

The first thing you very often see in an agent system is tuning the role—setting the role for the engine or the LLM that you’re talking to.

Example: “You’re an expert in all things Ryan Reynolds” (which we all should be, if you ask me).

2. Personality

These start to sound like the same thing if you say it too close to one another, but you can set the temperature essentially of the agent that you’re talking to.

Example: “You’re very talkative, you’re too talkative, and you hate it.”

We can all start to imagine what we might get back from a system that’s really an expert on Ryan Reynolds and talks too much but hates to talk too much.

3. Request

This is just basically the stuff that you and I type into ChatGPT. To an agent system, it’s basically the final request or the executable aspect of what you’re trying to get out of that agent.

If you have an agent that you’re building and you’re setting all these rules, you probably wanted it to do something. This is the “what do you want it to do?”

4. Format

We all know about format. I bet many of us don’t use it explicitly, though. We’ve probably used it a few times by saying something like “return me a poem” or “write me a limerick.” (Y’all are still asking for limericks, right? Those are fun.)

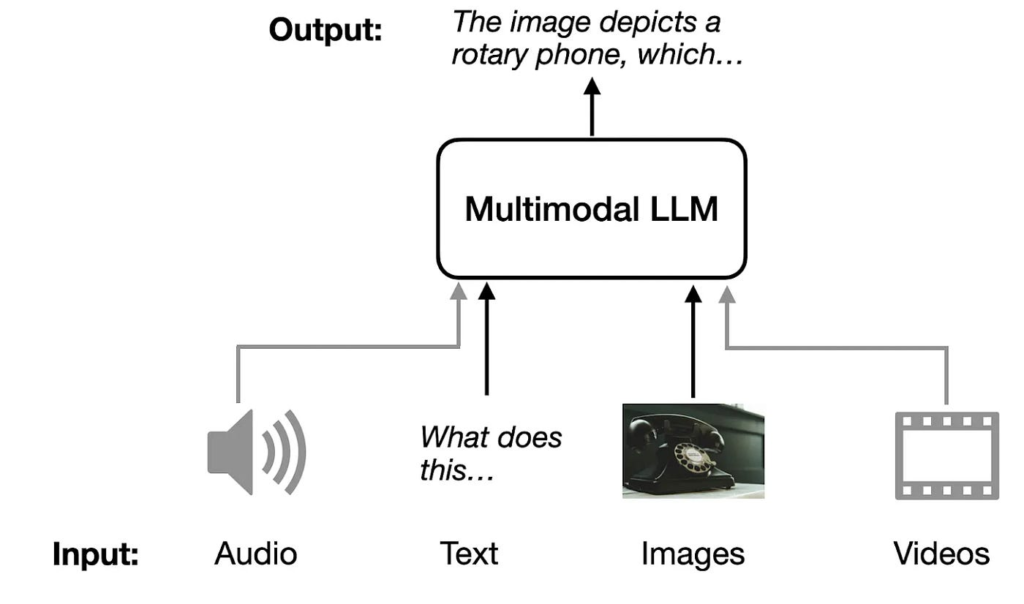

We might say “give me an image.” Some of these multimodal models can do audio, can do images. There’s a lot of format types that you might not necessarily think are format.

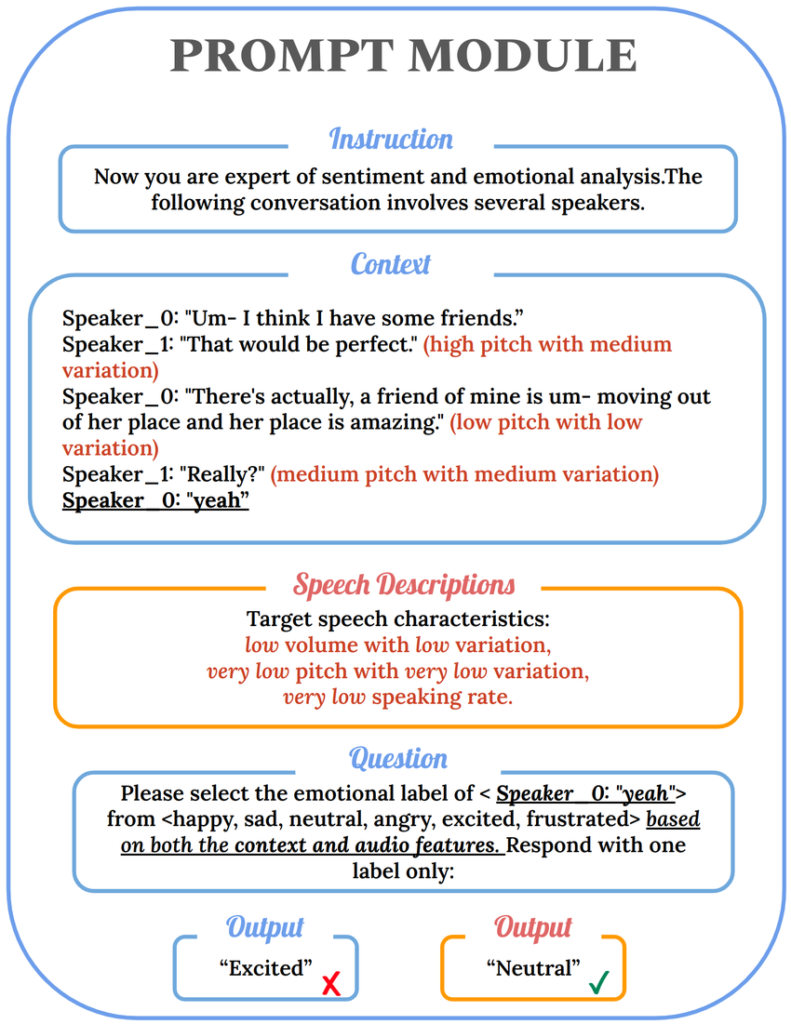

This is where examples come in, and examples are truly, truly important to the way that you would do prompt engineering.

If you do not give examples, the model has to figure out how it might give you the response back. If the format that you’re looking for is important enough to you, you can simply say, “Here’s two good examples and here’s two bad examples of answering these kinds of questions.”

Almost certainly that kind of fine-tuning at the prompt level will give you better results. So if you have an idea of what you are looking for, start using format with a couple examples and I almost guarantee you’ll see its value.

5. Constraints

Many people don’t explicitly use these, but we do use them. Remember, we’re separating all of these things not because they’re actually unique things—it’s actually kind of part of the language that we use to talk to a natural language engine.

Example: “Never return a movie containing Ryan Gosling.” I mean, come on, obviously it’s Ryan Reynolds, please.

6. Eval

Evals are something that are very common in agentic systems where basically at the end of something you have another LLM call or another algorithmic system that says “Go take a look at what we got back. Make sure it’s in the right format. Make sure it passes the right message structure. Make sure all the movies contain Ryan Reynolds as an actor,” for example.

But you can also do this in your prompt, and it’s basically reasserting other parts of the prompt that you’ve already put in.

Putting It All Together: A Real Example

If you’re looking at this saying, “Well, this is really not special”—brilliant! You’re already doing almost all of this. All I’m really pointing out is each one of these can be independently tuned. And if you start separating them in a way that you know how to tune each one of them, your prompt responses will get much better.

I wanted to test this, so I took the breakdown above, gave it to ChatGPT as a screenshot, and said, “Make a prompt for me using that file.” And it really did a great job.

Here’s what it created:

Role: You are an expert in all things Ryan Reynolds Personality: You're very talkative—maybe even too talkative—and you hate that about yourself Format: Provide responses in a numbered list with brief explanations Constraints: Never include movies featuring Ryan Gosling Eval: Before responding, verify all movies include Ryan Reynolds as a cast member Request: What are the five best action movies of the last 5 years?

You can even write your prompts in this way if you’re creating custom GPTs or something like that. These kinds of prompts really start to help. And this is where you get into prompt engineering.

Prompt engineering and context engineering are so married that they’re almost the same thing in many cases. But you might imagine there is a unique prompt potentially going every single time, and the context may remain very static for different states.

Let’s see what we get for the five best action movies of the last 5 years from a very talkative Ryan Reynolds-loving system:

“You want the best five action movies of the last 5 years and they must star Ryan Reynolds? No Gosling allowed? Challenge accepted. I’ll keep it punishingly pun-filled, but sarcastic. And yes, way too talkative. My bad. But hey, when you’re in denial, you just keep going.

- Deadpool and Wolverine

- The Adam Project

- Free Guy

- Red Notice

- Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard”

Wow. All right. It definitely works!

Conclusion

So in a nutshell, that’s context engineering. As you heard, I was just separating things so that you can turn the dial on the different areas that really matter the most. And each one of them has a reason to be turned in different states.

Whether you’re building sophisticated AI systems or just trying to get better responses from ChatGPT, understanding these elements—memory, files, RAG, tools, and prompt engineering—gives you the power to fine-tune your interactions and get dramatically better results.

Start thinking of these as dials you can adjust. Test things out. See what happens when you’re more explicit about format, or when you add examples, or when you set a specific role. The difference can be remarkable.

- Context Engineering: The Secret Behind Every AI Conversation

- Zero to Python Hero – Part 6/10: Functions and Modules in Python

- Zero to Python Hero – Part 5/10: Essential Data Structures in Python: Lists, Tuples, Sets & Dictionaries

- Top 5 Skills Every Engineer Should Learn in 2026

- Zero to Python Hero - Part 4/10 : Control Flow: If, Loops & More (with code examples)

Author

-

Naveen Pandey has more than 2 years of experience in data science and machine learning. He is an experienced Machine Learning Engineer with a strong background in data analysis, natural language processing, and machine learning. Holding a Bachelor of Science in Information Technology from Sikkim Manipal University, he excels in leveraging cutting-edge technologies such as Large Language Models (LLMs), TensorFlow, PyTorch, and Hugging Face to develop innovative solutions.

View all posts